In Oregon’s most urbanized, diverse area, the watershed has become a classroom

Drive north on 47th Avenue towards a Boeing hangar, and you’ll pass Whitaker Ponds Nature Park. The site was formerly a Chinook village called Neercherkikoo. Fifty years ago it had become an informal dump, acquiring enough bald tires to overflow every corner of nearby Les Schwab. The surrounding neighborhood is both industrial and residential. Semis grind down busy Columbia and Lombard Boulevards going to and from the airport, freeways, innumerable factories, shipping terminals, and the port. This place of grey impermeable cement, rubber, and jet fuel is one of the most densely populated, diverse, and urbanized areas in the state of Oregon. It’s also a living watershed.

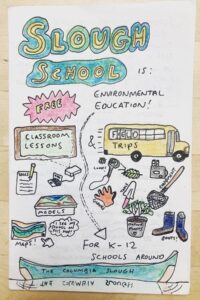

Jennifer Starkey erupts into delighted laughter at the sight of a bald eagle overhead, like she’s run into an old boisterous friend. She’s walking the half-mile loop trail through the black cottonwood forest around Whitaker Ponds and alongside Whitaker Slough, a channel of the Columbia Slough—no longer a dumping ground and now a vibrant natural area. Earlier in the day, she’d been at Sitton Elementary, planning field trips and lessons with an arts teacher. Starkey runs Slough School, a program of the Columbia Slough Watershed Council, which stewards this 19-miles-as-the-crow-flies urban watershed running from Fairview Lake in Gresham to Kelley Point Park near St. Johns.

Slough School functions as a gift and an invitation to teachers at Title I schools within the watershed—which means those with the highest low-income populations. Starkey focuses on elementary schools and classes that she can visit or host repeatedly. On Tuesdays, Wednesdays, and Thursdays, she offers free hands-on educational programs centered on the life of the Slough. Crucial to the design of Slough School is to ask teachers what’s important and listen to their needs, filling holes they otherwise can’t patch.

In addition to class visits, she hosts field trips, which are always free, including the bus. Sometimes she loads as many as 25 kids into canoes. She and students have replanted denuded farmland; harvested apples; studied native bees, water chemistry, and soil erosion; taken film photos of their friends in natural areas; dipped for aquatic macroinvertebrates; and more. She provides warm waterproof coats, boots, and gloves to keep kids warm as they slosh around outdoors under a dripping Portland sky. Across last school year, she delivered 198 classroom lessons, shepherded 68 field trips, and launched 556 kids into canoes.

“I want all the kids I work with to have a positive experience in a natural area,” she relays. Starkey had a transformative experience in high school as a student leader at Outdoor School. She found a sense of belonging. She knows that sensation is not readily accorded to most kids who live in this neighborhood. “It’s common for White people to forget how easy it is for them to be in a natural area.” Seventy percent of the students she works with are students of color. Before they go to Outdoor School, she wants to imprint the belief: “I belong here.”

Toward that end, one of her goals is to have students build their own direct relationships to these places.

“I want to introduce these places, [plants, and animals] with an understanding that the name we call it right now is not what it’s always been called,” she continues. Why do we call it Whitaker Ponds and not Neercherkikoo? She offers another example, looking up into the canopy: “I learned your name is cottonwood, but that hasn’t always been your name.” She teaches students to ask: Who are you? How did you get that name? What is my relationship to you? These questions lead to others: How do humans impact ecologies? How can we move from extraction to regeneration? How can we see ourselves as part of the life of the Slough?

Starkey begins to tell the history of how this land became the park it is today. Ed Washington, a Civil Rights leader and the first Black member of the Portland Metro Council, had grown up on the Slough in Vanport, a slapdash town created to house workers who’d moved to Portland to build warships during World War II. He was a kid when Vanport flooded, ruining homes and displacing residents, which included the majority of Portland’s Black community. City leaders knew Vanport was at risk but treated its population as expendable.

When Starkey teaches about Vanport, she has students take drawing notes. “It’s my goal to engage students for whom academics are hard in the classroom.” Understanding what happened in Vanport offers science lessons on river systems, snowmelt, flood plains, and how levees function. But of course, it’s also a story of our shared history.

Returning to Ed Washington, he knew firsthand about the systemic disinvestment in the neighborhoods around the Slough. In the 1990s, Washington worked with various agencies to acquire the land at the heart of the watershed, transform it into Whitaker Ponds, and reconnect residents to the water system coursing near them. He felt a strong sense of belonging and responsibility.

What can she do to help kids feel the motivation that Washington felt, Starkey asks? She believes that it begins with sustained, informed, interactive relationships to these places and the creatures who live in and near them. She points to the lumps on teenage fir tree bark filled with sap. “I love you,” she cries out to the first trillium of spring. Slough School exists to facilitate experiential learning and deep personal connections. “There are so many relationships to be had.”

RESOURCES FOR YOU! Many Slough School lessons are online and available to all. Starkey’s videos, presentations, coloring sheets, and maps are visually engaging and creative. She invites any teacher—and the students in all of us—to utilize them. Visit https://www.columbiaslough.org/slough-school-online to learn more.